Research

Overview

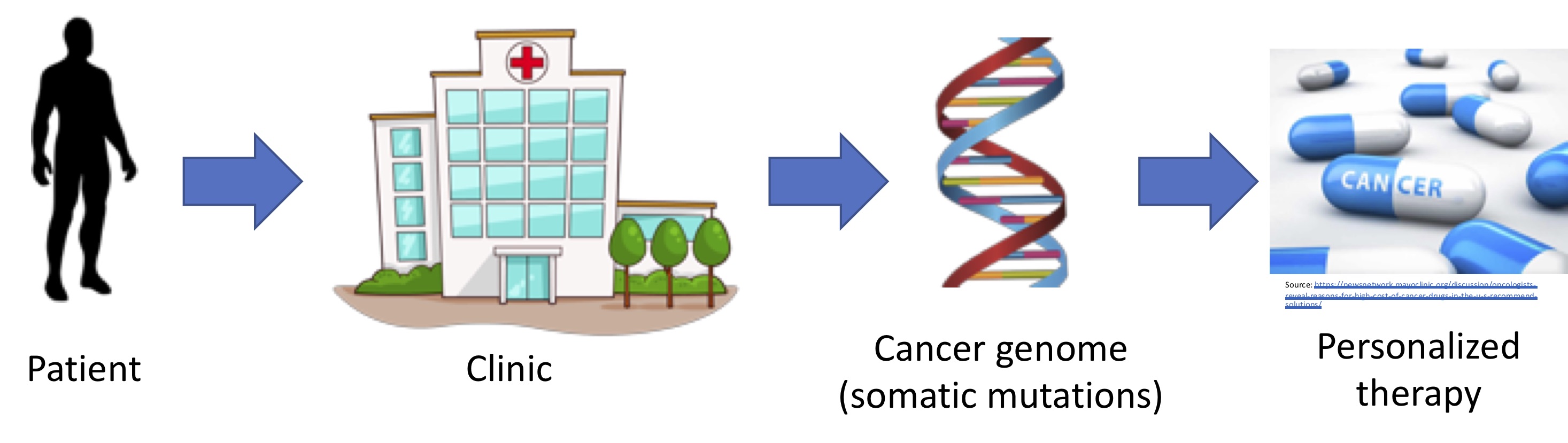

Cancer is a collection of diseases with many causes. This heterogeneity limits the efficacy of standard approaches that give the same treatment to large subpopulations of patients. The promise of a personalized approach to cancer therapy lies in expanding opportunities for treatment by identifying patients who are likely to respond but who do not meet the traditional selection criteria, and in predicting patients who will not respond so they do not endure unnecessary adverse effects or costs. Standard approaches to matching cancer patients with therapy have been coarse, relying on tumor histology (what the tumor looks like under a microscope), the tumor tissue-of-origin, and a handful of molecular markers.

To obtain a finer-grained picture, researchers are collecting vast amounts of molecular data from patients with cancer, with large public datasets recently becoming available. The challenge is to investigate this data to understand the functional state of the tumor and translate this knowledge into personalized therapy. Molecular data such as from DNA- and RNA-sequencing provide a lens on the perturbed cellular functions driving tumor growth, the interaction of the tumor with other cells in the body, and much more. However, molecular data is often noisy and high-dimensional with many (often unobserved) confounders. Thus, realizing personalized cancer therapy requires overcoming challenging computational problems.

Making headway on the promise of personalized cancer therapy requires making connections between key problems in cancer biology, statistics, and computer science. Our research group is especially innovative in that it combines a breadth of understanding of multiple areas with the depth of understanding necessary to connect core problems, develop a computational approach, and apply the approach to gain new biological knowledge. In that vein, our major research initiatives span three classes of cancer therapy, and span understanding the functional state of the tumor and translating molecular data into personalized therapy. To begin to tackle these challenges, we develop methods in many areas of computer science and statistics, including graph theory, probabilistic models, and machine learning.

Major research initiatives and approaches

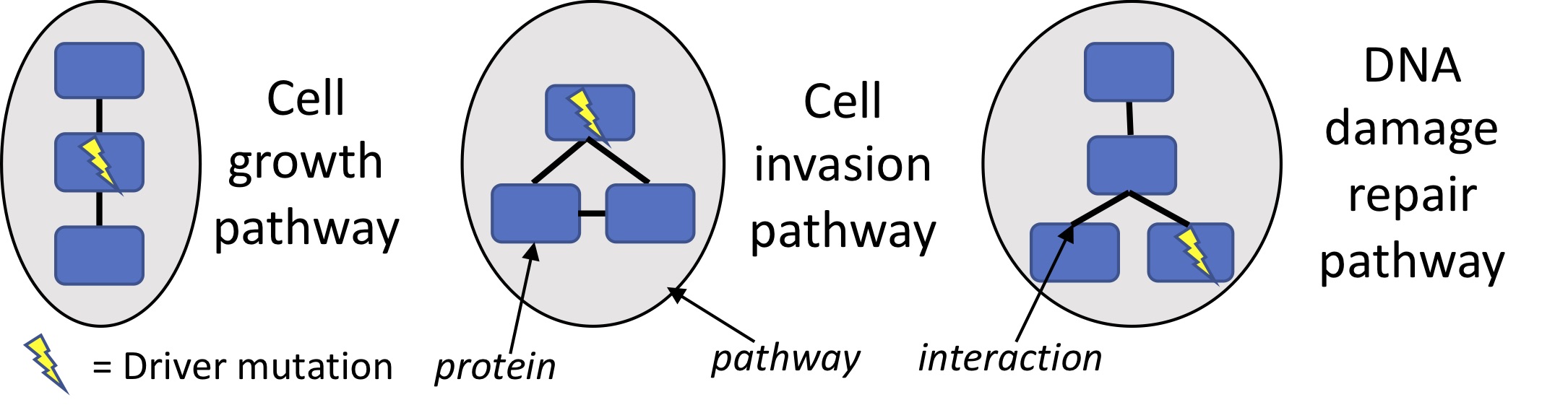

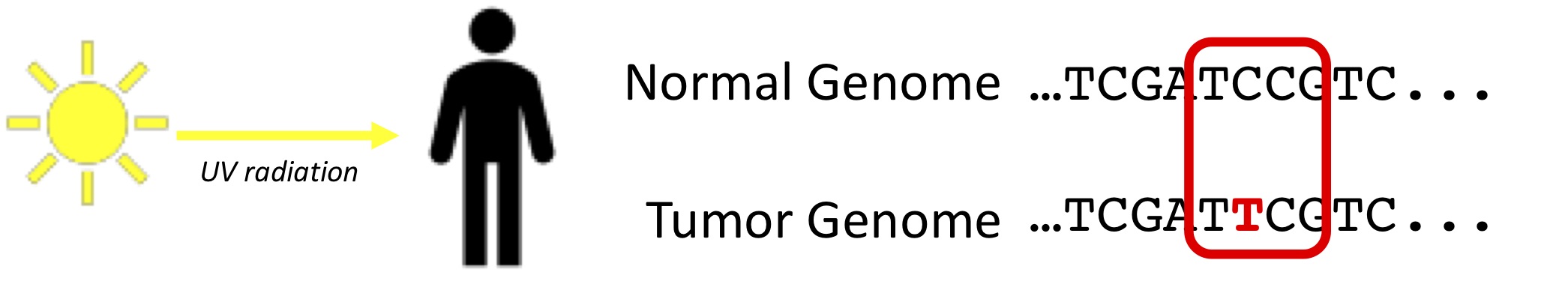

Our primary research focus is on understanding the causes and consequences of mutations in cancer. Cancer is driven in large part by somatic mutations that accumulate throughout the lifetime of an individual. Identifying the driver mutations that cause cancer can expand opportunities for targeted therapy, e.g. where a drug inhibits a driver gene that cancer cells rely on. Driver mutations target pathways -- each containing many genes that can be perturbed in many ways -- which makes distinguishing the few drivers from the numerous other mutations difficult. Our research seeks to address this challenge by developing methods to identify statistically significant combinations of driver mutations in biological networks [1], or with combinatorial optimization of statistical scores [2-3].

We also study cancer mutation datasets to understand the history of mutational processes shaping the cancer genome. Many successful cancer therapies work by causing DNA damage or inhibiting DNA damage repair, which cancer cells are less able to survive than healthy cells. Thus, identifying molecular markers for mutational processes such as DNA repair deficiencies is a priority. Large cancer sequencing projects have recently revealed dozens of signatures of mutational processes, each consisting of a different pattern of base substitutions. A major unmet challenge lies in characterizing the signatures with unknown causes. This is a difficult computational problem because dozens of factors affect the mutational process activity in a given cell, and combinations of factors sometimes leave similar signatures. Our approach to this challenge is to use probabilistic models of mutation signatures and their properties or covariates in order to distinguish similar signatures, discover rare signatures, and infer their underlying causes. One such property we are studying is sequential dependency along the genome [4], as some mutational processes cause mutations in localized clusters.

Our research also includes initiatives for improving to two other types of cancer therapy -- immunotherapy and synthetic lethal therapy -- that have become major success stories over the past decade. Immunotherapy works by harnessing a patient’s own immune system to destroy cancer cells, and has allowed patients with late stage cancer to make unprecedented recoveries. However, a minority of patients respond to the most common type of immunotherapy, many patients experience adverse effects, and the reasons for the differences in response are not yet well understood. Predicting which patients will respond is a particularly difficult challenge as it involves understanding the interactions of the tumor with the immune system, as well as the clinical history of the patient. As part of the Stand Up 2 Cancer and Microsoft Research Convergence 2.0 program, we seek to develop multifactorial models of response to immunotherapy, beginning with bladder cancers [5].

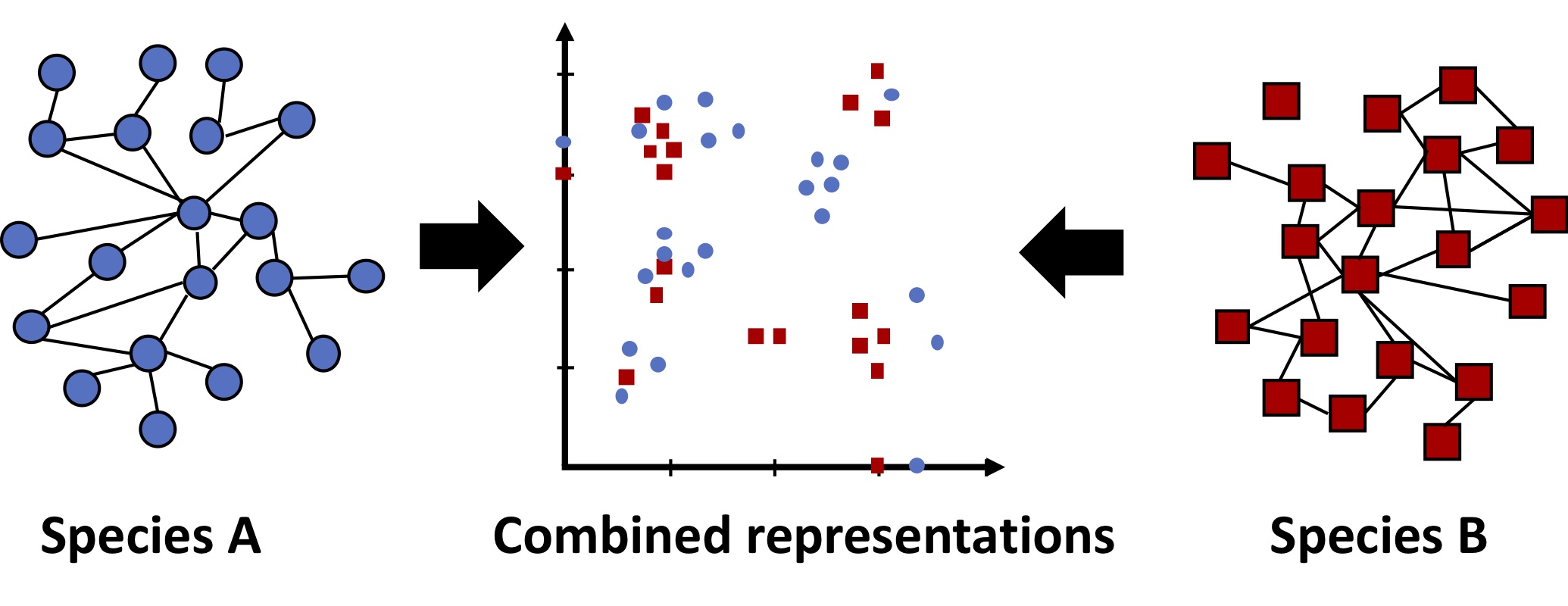

Another promising therapy is based on synthetic lethality. Some pairs of genes are pairwise essential (also known as synthetically lethal), such that a cell can live without gene A or gene B, but not without both. If gene A and B have a synthetic lethal interaction, a therapy could selectively kill the cancer cells with a mutation in gene A by inhibiting gene B. The challenge lies in identifying pairs of genes with synthetic lethal interactions, but comprehensive maps of such genetic interactions are only available in model organisms such as yeast. We seek to develop methods to prioritize which pairs of genes to test for interactions, leveraging information from species with comprehensive maps. Our first approach to this problem was to embed genes from different species in the same feature space using a multi-network graph kernel, and perform supervised learning [6].

Other topics of interests

Fairness, accountability, and transparency in machine learning. Recent advances in data-driven machine learning have led to its widespread adoption for building tools in areas such as natural language processing and computer vision. However, despite some of these tools being used by millions of people, there is currently a deficit of computational methods for ensuring these tools are fair or accountable. Consequently, machines often learn the bias encoded in their input data, from racial bias in image recognition to gender bias in word choice. We seek to develop methods to discover this bias in existing tools or models, and/or counter this bias either before or after the model is trained. Our initial work in collaboration with researchers at Microsoft Research New England examined biases in word embeddings and in image retrieval [7-8].

Relevant publications

- Leiserson*, Vandin*, et al. Nature Genetics (2015). doi: 10.1038/ng.3168.

- Leiserson*, Wu et al. Genome Biology (2015). doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0700-7.

- Leiserson et al. Bioinformatics/ECCB (2016). doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw462.

- Huang*, Sason*, Wojtowicz*, et al. bioRxiv (2018). doi: 10.1101/392639. (in revision)

- Leiserson et al. PLOS ONE (2018). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208422.

- Fan et al. Nucleic Acids Research (2019). doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz132.

- Swinger, et al. AAAI/ACM Artifical Intelligence, Ethics, and Society (2019; to appear). arXiv: 1812.08769.

- Dwork, et al. ACM Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (2018) PMLR 81:119-133.

Key Collaborators

Funding